Lincoln on Leadership: A Book Review for School District Leadership

Are you looking for a short read that provides clear and practical examples of effective leadership for personal development? If so, you would benefit from studying Donald T. Phillips’ book, Lincoln on Leadership: Executive Strategies for Tough Times, an analysis of the executive leadership traits embodied by the 16th president of the United States. In his review of President Abraham Lincoln’s example, Phillips takes the perspective of one discovering a rich tapestry of leadership skills hidden in plain sight. His approach makes the reader feel like they are learning about the well-studied leader for the first time.

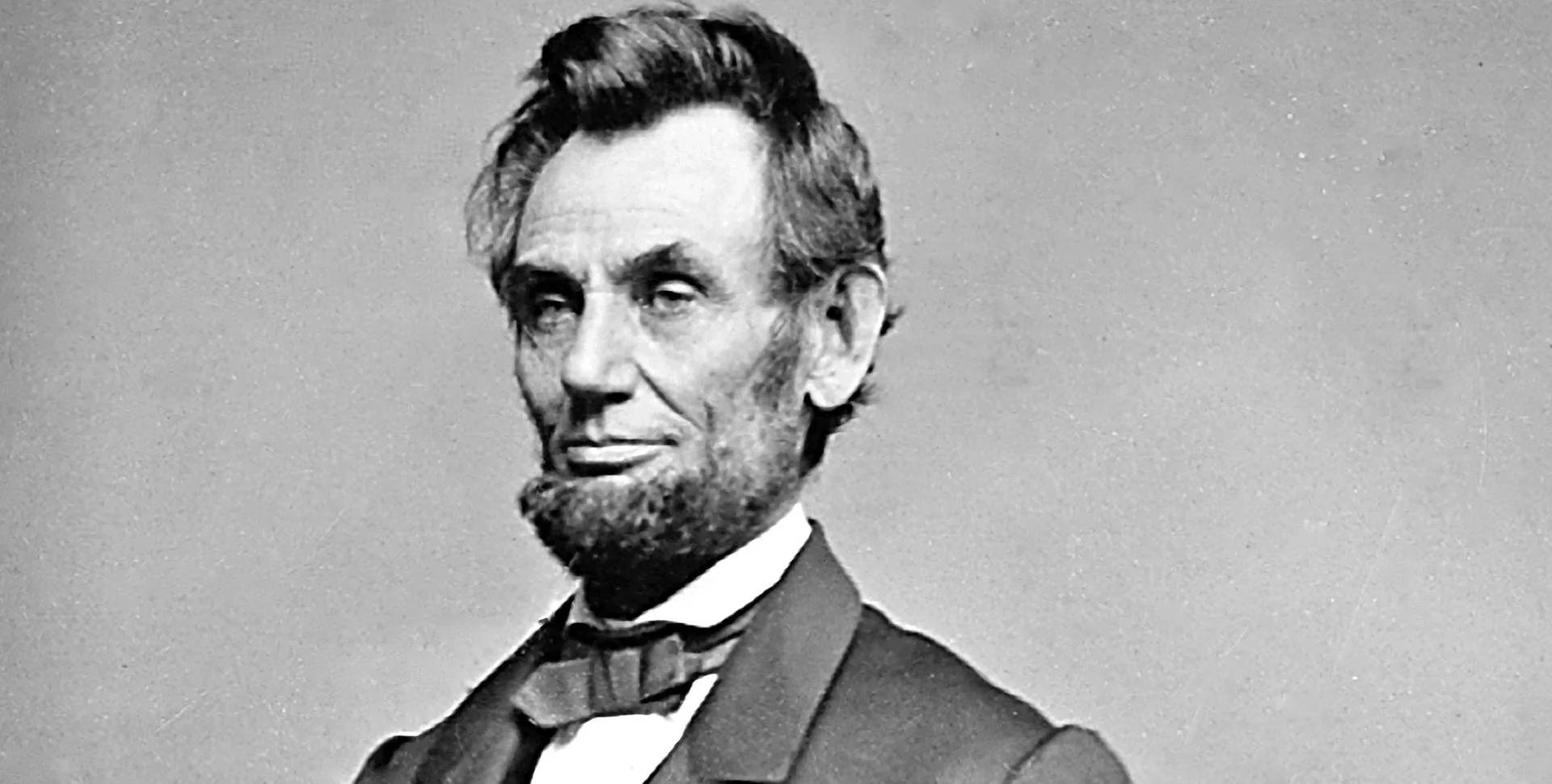

Abraham Lincoln, United States 16th President

Are you looking for a short read that provides clear and practical examples of effective leadership for personal development? If so, you would benefit from studying Donald T. Phillips’ book, Lincoln on Leadership: Executive Strategies for Tough Times, an analysis of the executive leadership traits embodied by the 16th president of the United States. In his review of President Abraham Lincoln’s example, Phillips takes the perspective of one discovering a rich tapestry of leadership skills hidden in plain sight. His approach makes the reader feel like they are learning about the well-studied leader for the first time.

Phillips researched thousands of primary sources including letters, recorded accounts, and interview transcripts from people who worked directly with the President. He also highlighted several of Lincoln’s letters and quotes throughout the book. The use of the actual words of Lincoln both illuminates and validates Phillips’ claim that he possessed modern leadership traits that are applicable in today’s business and workforce environments. Phillips organized the book into four sections that address effective leaders’ ability to build relationships, personal character traits and values, endeavors to lead, and communication skills.

In the first section, entitled “People”, Phillips outlines a critical strategy that leaders may use to build meaningful relationships with subordinates. Specifically, he describes Lincoln’s example of engaging those around him to empower them, build strong alliances, and cultivate a sense of loyalty. Phillips’ second section, “Character”, highlights how Lincoln’s uncompromising policies of honesty and integrity won over many of the strong personalities he confronted. Phillips encourages today’s leaders to align their actions, values, and character to influence the character of their organizations, as Lincoln influenced the character of his nation. In the third section, “Endeavor”, Phillip teaches leaders to emulate the way that Lincoln encouraged innovation and sought generals who craved responsibility and took risks. He also provides rich, historical examples of the President’s decisiveness to show that a leader has to be decisive, set goals, and be results-oriented. Phillip's final section, “Communication”, puts President Lincoln’s charm and masterful communication style on display to emphasize the power and importance of effective communication for leaders. He points out how mastering the art of public speaking, developing the ability to influence people through conversation, and communicating a strong vision are at the essence of executive leadership.

Potential Impact for School District Leaders/ Reflection and Recommendation

Lincoln on Leadership achieved Donald T. Phillips’ goal of illustrating in clear and concise detail the leadership prowess of President Lincoln. Phillips’ book elucidates the leadership principles that Lincoln demonstrated throughout his life and identified why executive leaders today should implement them. Throughout the book, Phillips frames Lincoln’s leadership traits in a way that aligns to the work of the Superintendent as the chief executive of a school district. Phillips’ work should equip any school leader with solid leadership principles and would serve as a reminder that leaders must embody, communicate, and affirm high values and character. Additionally, Lincoln on Leadership lays out a straightforward blueprint for superintendents to build essential relationships in their school systems and the communities they serve.

Finally, a superintendent would benefit from studying Lincoln on Leadership in great detail to better understand how the 16th president of the United States was able to lead in times of crisis when leaders are needed most. It could be argued that most superintendents would have already cultivated many of the leadership traits presented by Phillips and that it would be more relevant for aspiring leaders or first-time superintendents. However, Lincoln on Leadership can still serve as a refresher for a superintendent and should be read by all educational leaders.

Reference

Phillips, D. T. (1992) Lincoln on Leadership: Executive Strategies for Tough Times. New York: Warner Books. (ISBN 0-446-39459-9)

If you found this post valuable, please consider supporting my work as an independent creator.

The Role of the Community in Education

In today’s economically and culturally diverse society it is vitally important that educators and community leaders find clarity on each other’s role in supporting our students' academic achievement (Anderson-Butcher et. al., 2010). This need is only intensified when we consider the context of the required school reform actions brought on by No Child Left behind (NCLB) and Adequate Yearly Progress (AYP) accountability measures. However, the formation of effective school and community partnerships is usually defaulted to the responsibility of the schools and often are not established due to communication and expectation barriers (Hands, 2010). With increasing reports of economic disparities between parents and communities of high performing schools and those of schools in need of academic achievement improvements, various factors have served as barriers to strong school and community partnerships.

1420155098_full.jpeg

In today’s economically and culturally diverse society it is vitally important that educators and community leaders find clarity on each other’s role in supporting our students' academic achievement (Anderson-Butcher et. al., 2010). This need is only intensified when we consider the context of the required school reform actions brought on by No Child Left behind (NCLB) and Adequate Yearly Progress (AYP) accountability measures. However, the formation of effective school and community partnerships is usually defaulted to the responsibility of the schools and often are not established due to communication and expectation barriers (Hands, 2010). With increasing reports of economic disparities between parents and communities of high performing schools and those of schools in need of academic achievement improvements, various factors have served as barriers to strong school and community partnerships.

A common factor impeding the formation of strong schools and communities partnerships is the lack of contextual understanding of the dynamic nature of the interactions between schools and their surrounding environment (Hands, 2010). Hands (2010) states, "While schools and communities are distinct entities, the borders between them are permeable" (p.191). This is demonstrated very clearly in larger school districts with diverse economic and cultural communities. Each community has diverging expectations of support from the schools which influence the school's efforts and expectations of the community (Goldring & Berends, 2009). The cycle of influence can change as the school leadership or community resources change.

A key factor in revealing some of the school and community expectations can be observed through the collection and measurement of data regarding parent and community opinions and views on being involved in the decision-making process. Proper collection and use of the data from tools such as climate surveys can be useful in informing an array of school reform and school improvement efforts. According to Thapa et. al (2013), "In the United States and around the world, there is a growing interest in school climate reform and an appreciation that this is a viable, data-driven school improvement strategy that promotes safer, more supportive, and more civil K–12 schools” (p.357). Public opinion surveys could also be employed to identify community priorities, attitudes, and opinions. In my district, several of our schools and programs, such as our Career and Technical Education (CTE) program have established advisory committees to welcome community involvement in many educational decision-making efforts. As a result, we have been able to not only gather a deeper understanding of the communities perceptions of the district, but we have also shared the responsibility of contributing to the success of our students and academic programs.

Encouraging parental and community involvement in the decision-making process of an instructional improvement committee can definitely be both beneficial, but it would require a higher level of accountability. Often we can become so engulfed in the state accountability measures that we lose sight of how we are accountable to our first level customers, students and parents. In my district, we are required to have parent and community involvement on our Campus Improvement Committees (CICs), but it is interesting to me, how that involvement actually plays out. I am fascinated by how differently we, educators and educational leaders, define parental involvement. This is also because every community has different means and constraints that impact their ability to be “involved” in the schools. In my experiences, these differences in community coupled with our differences in defining involvement often lead to a disconnect in expectations and communications.

As an urban educator, I have witnessed many expectation discrepancies between school and community that end up negatively affecting students. For example, many teachers and administrators, due to a lack of expected parental involvement, have found it necessary to provide various supports for students and parents that go beyond the traditional K-12 setting. In my humble opinion, this action, in the larger sense, has done more damage than good. Now I am not saying that when a school gets involved in grassroots efforts within the community that all students and parent are harmed, but I do believe those types of efforts have adjusted the communities expectations of the school's responsibilities. This could lead to a different kind of scrutiny when schools are not able to effectively take on these additional burdens, and it causes some communities to feel absolved of some of the need to be an active participant in the education of our students.

On one hand it is evident that developing partnerships between schools and the community have a significant impact, but on the other hand, the process of establishing partnerships is a challenge due to the differences in expectations, resources, and other contextual influences (Hand, 2010). To this end, both schools and the community need to work together to share the responsibility of working through these differences to find common ground and ultimately improve student achievement in every community and intended by NCLB.

References

Anderson-Butcher, D., Lawson, H. A., Iachini, A., Flaspohler, P., Bean, J., & Wade-Mdivanian, R. (2010). Emergent Evidence in Support of a Community Collaboration Model for School Improvement. Children & Schools, 32(3), 160-171. doi: 10.1093/cs/32.3.160

Goldring, E. & Berends, M. (2009). Leading with Data: Pathways to Improve Your School. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Hands, C. M. (2010). Why collaborate? The differing reasons for secondary school educators' establishment of school-community partnerships. School effectiveness and school improvement, 21(2), 189-207.

Thapa, A., Cohen, J., Guffey, S., & Higgins-D’Alessandro, A. (2013). A Review of School Climate Research. Review of Educational Research, 83(3), 357-385. doi: 10.3102/0034654313483907