Exposing K-12 Schools Achilles' Heel

One of the most prominent issues that affect K-12 public schools as social organizations is a propensity to operate from the position that "We're going to do what we've always done because that's what we've always done." This notion is pervasive and widely unrecognized and acknowledged. Likewise, the habits that arise from this notion are formed subtly yet become deeply ingrained in (and debilitating to) the system operations. Practically speaking, systems tend to employ practices or habits that are undocumented in policy, unsupported by data and are not effectively educating students. The negative consequences of this mindset include parents withdraw their students in favor of the more flexible and responsive systems of private and charter schools; educators' efforts are constrained and academic performance is weak; the best and most innovative educators are recruited by other systems or possibly even leave the field; and students suffer because they are not prepared to meet the demands of an ever-changing society. Left unchecked, poor organizational habits within systems ultimately weaken our nation's ability to compete on the global level.

090720_Tweens

One of the most prominent issues that affect K-12 public schools as social organizations is a propensity to operate from the position that "We're going to do what we've always done because that's what we've always done." This notion is pervasive and widely unrecognized and acknowledged. Likewise, the habits that arise from this notion are formed subtly yet become deeply ingrained in (and debilitating to) the system operations. Practically speaking, systems tend to employ practices or habits that are undocumented in policy, unsupported by data and are not effectively educating students. The negative consequences of this mindset include parents withdraw their students in favor of the more flexible and responsive systems of private and charter schools; educators' efforts are constrained and academic performance is weak; the best and most innovative educators are recruited by other systems or possibly even leave the field; and students suffer because they are not prepared to meet the demands of an ever-changing society. Left unchecked, poor organizational habits within systems ultimately weaken our nation's ability to compete on the global level.

To address this issue, organizations should establish habits of reflection at the teacher and administrator levels so they can begin to make the connections between practices and outcomes more real or direct. Examples of these habits include coaching conversations between teachers and teacher leaders; feedback shared by teachers in professional learning communities; and collaborative administrators dialoguing about effective practices. Creating opportunities for reflection not only helps teachers and administrators, but it also promotes an environment and culture in which all stakeholders can challenge organizational habits. In addition to reflection, schools should re-evaluate policies to determine if they are being followed and if they are in support of their short-term and long-term goals. The only thing worse than a bad policy is a good policy that is not followed; nevertheless, both allow schools the continue practicing bad habits. Schools also need to review what is policy and what are actual practices in order to expose unwritten organizational habits. This involves questioning a policy's clarity and usefulness, evaluating desired outcomes using research and measurement tools, and working to redefine policies based on their findings. Lastly, K-12 public schools should establish protocols for using data to make decisions, set goals, and evaluate programs or outcome. This process should address the questions, "What do we do with the data we receive", "What questions do you ask", and "What data sets are most relevant?" Far too often K-12 schools are data rich but information poor; school systems must reach the point where they see the issues clearly and are able to mobilize resources to implement real solutions.

K-12 schools are charged today with the task of educating a quickly changing student body to face the challenges of a dynamic workforce and society. If schools implemented these practical solutions with fidelity, not only will they be able to finally dismantle the debilitating organizational habits that plague them, they will be able to change in the appropriate time frame necessary to respond to the needs of today's student.

Time for A PLC Refocus

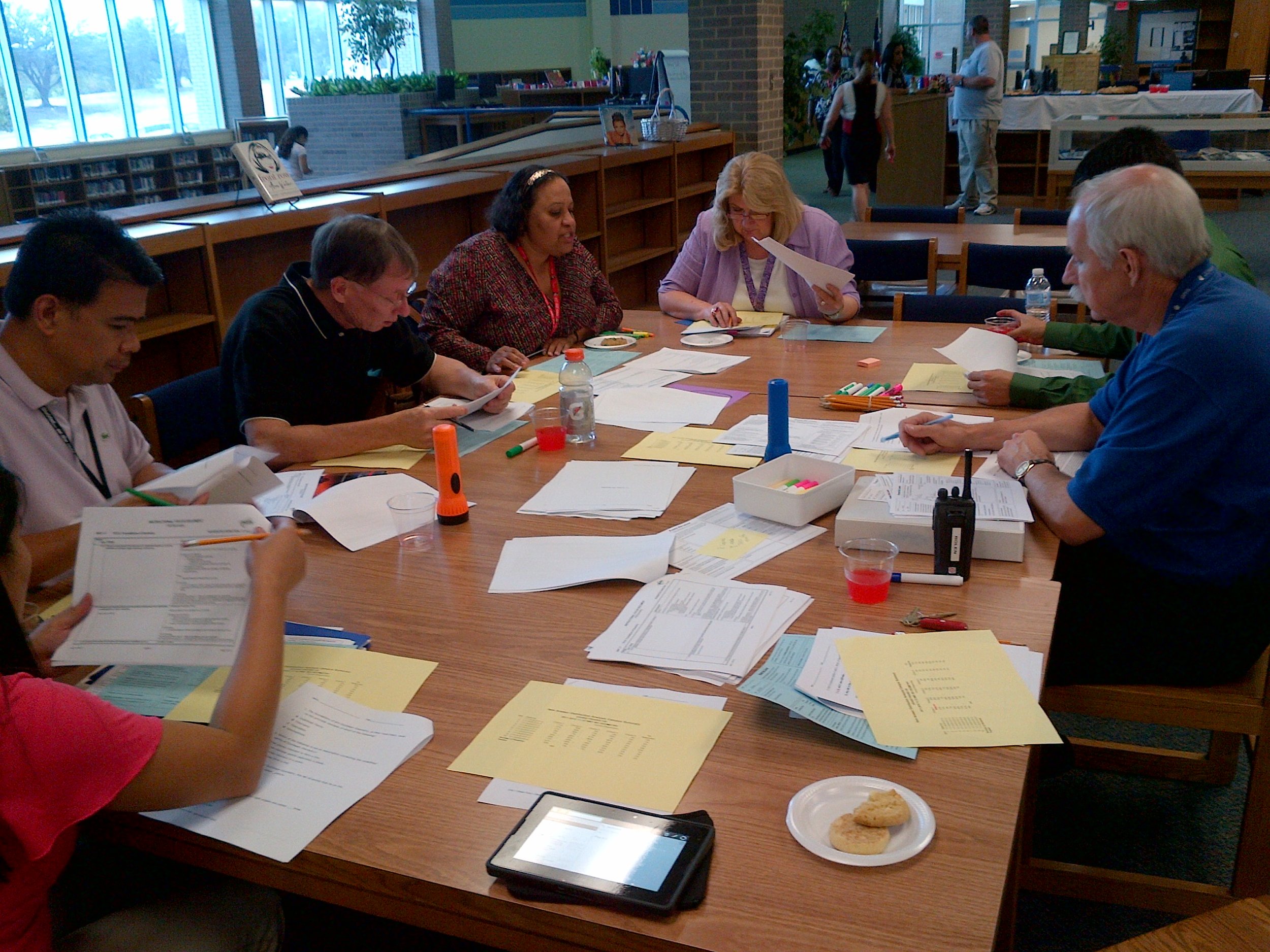

Throughout an academic year, an instructional coach can find themselves going through cycles when working within professional learning communities (PLCs). When you reflect on the function of your PLC group, it is easy to see how the PLC could loose focus on the main goals. If the facilitator of the PLC doesn't recognize the need for re-calibration early enough even the most dedicated group of educators could become completely derailed and discouraged. As a result of experiencing PLC train wrecks as well as PLC success stories, I developed the following short refocusing exercise for the instructional coach or PLC facilitator to implement with a team of teachers. Every team has different dynamics, but usually, around mid-year, a very observant instructional coach could begin to notice the signs that suggest it is time for a PLC Refocus. This is simple in concept, but it requires skillful execution. If the timing is right and the approach is non-judgmental the PLC could benefit greatly. Give it a try, and share your results.

Revisiting PLC Norms

Present each question to the entire team for collaboration and ask them to share their thoughts one question at a time. Ask clarifying questions like those below to simplify the group’s responses and collect their final answers.

What will you say and do when you disagree?

What will you say and do when you are not comfortable with a concept or teaching strategy?

What will you say and do when a colleague achieves a goal?

What will you say and do when a colleague doesn’t follow the PLC Norms?

An Assessment Accountability System Deferred

Recently the Texas Commissioner of Education, Michael L. Williams, announced that he was deferring implementation of a 15 percent grading requirement for the 2012-2013 school year. This news was received by the vast majority of educators across Texas with jubilation and relief. To put this reaction in context, you would have to understand the policy’s origins and scope. When the state of Texas decided to upgrade its assessment and accountability system in 2009, it included a ruling that made a student’s score on the State of Texas Assessments of Academic Readiness (STAAR) end-of-course examinations count toward15 percent of the student’s final grade in each tested subject area.

Now at first glance that would seem alarming, but when you consider the fact that students would be required to take several more assessments with more rigorous content and testing conditions, it became a serious anxiety accelerant for school administrators and educators. Commissioner William’s decision marks the second year the rule has been deferred. In the 2011-2012 school year, more than 1,100 of the state’s more than 1,200 school districts notified the Texas Education Agency that they would be selecting the voluntary deferral option.

Even though school systems have been given a reprieve with regard to the 15% grading requirement, students still must take all STAAR tests and meet all requirements for graduation.Even though most of the state appears to be finding a resolution, I am troubled by the majority reaction and am left with several yet-to-be answered still questions for theTexas Education Commissioner and K-12 School system educators throughout the state.

Why do we have so many conflicts with the 15% rule in the first place?

Who is looking into the nearly 100 out of the 1200 independent school systems that did not request a deferral of the 15% ruling during the first year of implementation, and how are these school system fairing? What led them to reject the deferral?

What does all the conflict with the 15% ruling really reveal about the Texas Educational System?

In summary, I am left with wonderments of the potential of the new state of Texas assessment and accountability system. One can not help but notice how that the system is being altered from what its planners originally intended. This is not to say adjustments are not needed, but the goal is to improve student achievement, all of these backtrackings no the 15% rule could be the proverbial beginning of the end. This end is the political dismantling of a once-promising state assessment and accountability system that supports more rigor and better student preparedness for their post-secondary endeavors. Perhaps we are simply witnessing an assessment accountability system deferred.